Task F: Elements of Effective Teaching that Include Risk Management and Accident Prevention

– risk management

Teaching risk management tools, including:

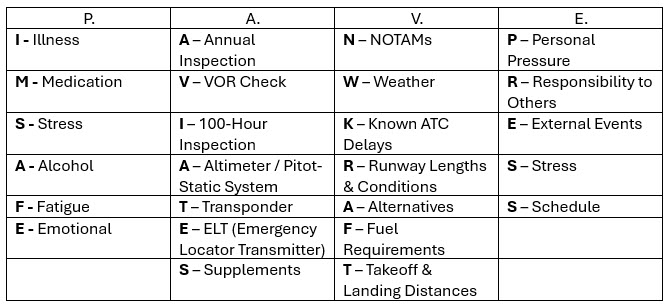

a. PAVE checklist: Pilot/Aircraft/enVironment/External Pressures

b. FRAT: Flight Risk Assessment Tools

The FAA emphasizes Risk Management and Single-Pilot Resource Management because effective decision-making skills are fundamental to safe flight.

The Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK) shows that pilots who receive structured Aeronautical Decision Making (ADM) and Risk Management (RM) training make significantly fewer judgment errors. This supports a key Fundamental of Instruction (FOI) principle that good judgment is a learned behavior shaped by motivation, experience, and cognitive development.

Risk management provides a systematic method for identifying hazards, assessing risk, and applying controls throughout every phase of flight. It reinforces higher-order thinking skills, self-assessment, and sound judgment. The FAA stresses that risk cannot be eliminated, but it can be managed through deliberate analysis and informed decision-making.

Single-Pilot Resource Management (SRM) extends these concepts to single-pilot operations, where workload, automation, navigation, and passenger pressures must be managed without crew support. Tools such as the PAVE checklist help pilots maintain situational awareness, prioritize tasks, and use available resources efficiently.Solo Cross-country: A Flight Lesson in Risk Management

“A Flight Lesson in Risk Management”

Written By R. Maclyn Stringer

Ethan, a private pilot student in his mid-twenties, arrived at our flight school early in the morning, looking excited for today’s lesson. It was not just a lesson; it was scheduled, again, to be his first cross-country solo flight. Hoping that after several delays due to weather, this was going to be the day.

“Good morning, Ethan,” I said. “It looks like the weather is finally going to cooperate with us.”

“I think so.” He responded with a smile.

“Do you have your weather and navigation briefing completed as we discussed?”

“Oh, that and more,” Ethan responded, looking towards me. “With all the delays, I have had plenty of time to create a well-prepared cross-country briefing for you.”

We walked upstairs to one of the school briefing rooms, which had a large desk and whiteboard. I set my coffee on the table and took a seat in one of the black, well-used, reclining chairs while Ethan walked to the front of the room, unpacked his backpack, placed his EFB and notebook on the table, and then stood at the whiteboard.

“Not only do I have a weather and navigation briefing for you, but I studied up on risk management and thought you would like to hear what I learned.” He stood at the front of the room, uncapped a marker, and in large block letters wrote one word on the whiteboard: PAVE.

Wow, I thought to myself. A student pilot briefing me on the PAVE checklist. We have discussed PAVE, but have not gone into great detail. Let’s see where this is going.

Ethan looked at me and said, “Alright, I’m the PIC, the pilot in command of this flight, and I’m safe. Before we talk about anything else, I need to confirm that I’m in a safe condition to fly.” Beneath the letter P, he wrote IMSAFE vertically and began working through each element.

Looking back at me, he pointed to each letter as he wrote each word and explained, “Illness: No symptoms, I am feeling great! Medication: I have not taken anything. Stress: Moderate due to the excitement of embarking on this cross-country alone. Alcohol: None consumed. Fatigue: I had a good night’s sleep after finishing this briefing.” Smiling at me. Then he continued, “Emotional: I am focused but slightly nervous.”

I nodded. His assessment seemed to be honest.

Pointing to the letter A, Ethan looked to me and said, “A stands for airplane. I was able to find all the information about the airplane in the maintenance logs. Brittany, at the front desk, was kind enough to show me where they were and how to read them. “Anyhow, before I am allowed to take this flight, I have to ensure the aircraft is airworthy. With that, I have to ensure the aircraft.” Pointing to the A in aviates, “has had an annual inspection.” Again, he ran through each item one by one, writing the term that each letter represented.

“Annual inspection completed last month.” Pointing to the letter V, he said, “VOR check within 30 days if using the airplane in IFR conditions, which I have no intention of doing at this time.” He said with a smile, 100-hour inspection, due in 20 hours. The altimeter and pitot-static system inspection must be completed every 24 months; this was completed during the annual inspection. Transponder, good. ELT, inspected two weeks ago, and all of the supplements are current, including the GPS database.”

He paused for questions. I intentionally offered none. His confidence grew.

“The next letter in our PAVE checklist is V. and, believe it or not, V stands for environment. The ‘en’ is silent… Vironment” he stated with a smile. “Here we have another acronym, NWKRAFT.” Ethan then wrote NWKRAFT vertically beneath the V on the whiteboard.

“NOTAMs checked. No runway closures along my route. I reviewed the weather, and it is forecasted to be mostly clear with light winds, but there is a potential for afternoon storms along the route. I should be back here before those storms develop. Winds aloft are manageable. I do not need to worry about ATC delays since I am VFR. The runway lengths at both airports exceed my takeoff and landing requirements by a wide margin. I looked at a few alternates along the route. Fuel, I planned 90 90-minute reserve. Takeoff and landing distances already calculated and exceed performance requirements.”His logic was sound. His mitigation regarding afternoon storms showed he understood that conditions today were not static.

Ethan continued, “Finally, we reach the E in our PAVE checklist, which stands for external pressure. This acronym assists in recognizing and managing psychological and operational pressures that could cause unsafe decisions.” He then turned to the whiteboard and wrote ‘PRESS’ vertically below the E. Looking at me and pointing to the whiteboard, he said, “PRESS,’

As he wrote the word for each letter, he explained. “I have no personal pressure to complete this flight. Responsibility to others, just you.” Looking at me, “because I want to perform well. No external events are pushing me to hurry. Stress is minimal. Schedule pressure is low since I planned for plenty of time before the weather builds.”

When he finished the PAVE briefing, he capped the marker, stood next to the whiteboard, and looked at me. “So that is my overall risk assessment. What do you think?”

“This is impressive, Ethan,” I told him.

Taking a seat, he said, “Now I’d like to review the FRAT.” He handed me a printed copy of the FAA Flight Risk Assessment Tool, which can be found at (https://www.faa.gov/general/flight-risk-assessment-tool-frat-faa-safety-team).

He had scored each item thoughtfully, not simply choosing the lowest values. Weather earned a mild risk score due to forecast convective development. Pilot experience added a small risk factor because this was his first solo cross-country. Each score was justified, and the total fell solidly into the green.

Now it was time for me to ask thought-provoking questions.

“Ethan, let’s say halfway to your destination, the scattered clouds begin building ahead of schedule, yet the cloud bases remain high. The visibility forward looks reduced. What do you do?”

Rather than jumping to an answer, he folded his arms on the desk and then responded.

“I’ll turn around. I’m not going to continue hoping it gets better.”

“Good.” I pushed further with another question.

“Your outbound leg is east. The weather typically comes from the west. What if you see the storms building on your return leg?”

Ethan responded, “I’ll land and give you a call.”

“What if your fuel burn ends up higher than expected?” I asked

Ethan responded, “I land at my planned alternate, top off, reassess the weather, and continue only if conditions support the flight. But with my 90-minute reserve, I should have enough.”

I asked another question, “What if a TFR pops up mid-flight?”

Ethan responded, “I will be on with flight following, hopefully they will let me know. I also checked the NOTAMs and will check again before departure, but if something appears en route, I’ll divert around it or land and wait for clarification.”

In each situation, he demonstrated structured decision-making using the tools he had laid out.

Then I presented the final complication.

“You arrive at the airport and find a last-minute text from your family saying they plan to celebrate your accomplishment this afternoon. They’re excited and already making plans. Does that affect your go/no-go decision?”

He smiled. “I’d like to impress them, but I’m not letting that drive the flight. If the weather or anything else changes, safety wins.”

That answer told me everything I needed to know. Not because he said the right words, but because he understood the implications of external pressure. That level of self-awareness is a cornerstone of accident prevention.

I sat back in my chair.

“Ethan, your briefing was thorough, your risk assessment was sound, and your mitigation strategies were realistic. Before you go, let’s review your navigation plan, fuel plan, and radio procedures. But from a risk management standpoint, you’re ready.”

His face lit up. He opened his EFB and began outlining the route, performance numbers, and alternate strategies. The preparation he showed today was not just about passing a flight requirement; it was about shaping his mindset for the rest of his flying career.

Leave a Reply