TASK F: ELEMENTS OF EFFECTIVE TEACHING THAT INCLUDE RISK MANAGEMENT AND ACCIDENT PREVENTION

Hazardous attitudes are among the FAA’s most critical safety concerns. While technical proficiency is essential, poor aeronautical decision-making is often rooted in hazardous attitudes that cause many preventable accidents.

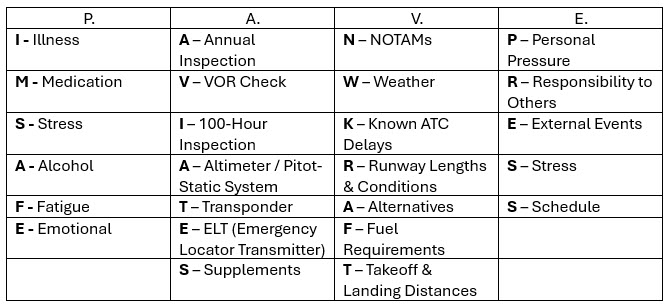

The FAA identifies five hazardous attitudes: anti-authority, impulsivity, invulnerability, macho, and resignation. Each comes with an antidote designed to reshape how pilots perceive risk and make decisions under pressure. When a pilot thinks “I can do it” or “It won’t happen to me,” they’re more likely to push weather minimums, stretch fuel reserves, or exceed their personal minimums.

Effective instruction must address not just what pilots do, but how they think. Recognizing and correcting hazardous attitudes helps prevent accidents before they happen.

“But I Could”

Combatting Hazardous Attitudes With Common Sense Antidotes

When William began training with me for his private pilot certificate, we flew nearly every day to accelerate his progress. He had a goal to be a commercial pilot as quickly as possible. But then his medical exam results threw an unexpected wrench into our plans. At first, the results appeared disqualifying, triggering an FAA review that put William’s training on hold for six months. Fortunately, after further evaluation, the issue was resolved.

Once back on the flightline, we accelerated his training, finishing everything in a few weeks. Subsequently, we coordinated his initial aviation check ride with a DPE outside our state, since arranging a timely local check ride has proven challenging.

Our flight school is located just east of the Rocky Mountains. The DPE William identified resided about 270 nautical miles from our home airport, about a 2.5-hour flight in the Piper Archer.

His check ride was scheduled for 8 AM. To prepare for it, William initially planned to leave the morning prior on a solo cross-country trip, allowing him enough time to arrive at his destination and then fly around the area to become familiar with the airspace.

On the morning of his flight, William and I met at the school as strong, gale-force winds struck our region, with Mother Nature enthusiastically demonstrating her power. Sitting in the pilot’s lounge, William checked the weather online and contacted Flight Service to speak with a weather briefer, while I sat quietly across the table without intervening, listening through the speaker. The choice to go on this trip was William’s, with my endorsement, of course. William requested to make this cross-country flight solo to meet with the DPE.

The briefer informed William that westerly winds of 40 to 50 knots with gusts above 70 were blowing from the surface through his planned altitude, extending several hundred miles to the east, and pilots had reported moderate to severe turbulence in the area. After hanging up, William reviewed his flight plan, studying his EFB and weighing different routes to his destination. He quickly ruled out flying west into the mountains or east through the plains.

“I’m going to wait out the windy weather for a few hours,” William said. “I think I can depart around noon and still have plenty of time to fly around the area.” I nodded and said, “Let’s wait and see what happens.”

Around noon, the winds calmed around our airport, though they remained strong to the north and across the eastern plains. As I sat on the couch, William approached me. “Mac, I can still make the flight today,” he said confidently, pointing at his tablet to describe his plan. “I’ll head east, then northwest to my destination.” “Really?” I said as I followed his finger along the route on his EFB. “That appears to be 100 miles east, then about 250 miles northwest?” I asked inquisitively, glancing up and noticing his determined expression. All morning, I noticed the hazardous attitudes building within him, fueling William’s urgent desire to fly to this check ride today. As a seasoned pilot and professional flight instructor, I understood it was time to ask questions.

“William, is flying two extra hours in windy, moderate-to-severe turbulent conditions sensible?” I asked.

“Two hours isn’t much,” William replied confidently. “We’ve flown together through turbulence. I can handle a few bumps.”

I couldn’t help but think how macho (I can do it) he sounded. A 50-hour student pilot thought he could handle gusting winds, low-level windshear, and turbulence.

“Have you considered the additional fuel and time required?” I questioned.

“With full tanks, I can complete the flight, with the required reserve,” William said confidently.

“How much headwind are you going to encounter when you head northwest, and how much additional time will be required?” I asked.

William looked baffled. “I hadn’t considered that, but I’ll figure it out and update the flight plan.” Displaying the hazardous attitude of impulsivity (“Do it quickly”) in his desire to get to his destination.

“Are you going to make this flight before sundown?” I pressed. “Have you accounted for any delays?”

William responded, “I’ll arrive about thirty minutes before sundown.”

“And what will you do if the sun goes down before you reach your destination? Are you allowed to fly at night as a student pilot?” I asked.

With an assured grin, he displayed invulnerability (it won’t happen to me). “I’ll get there.” After a few seconds, he continued, “And hey, you could give me a student solo night-flying endorsement.”

I shook my head negatively. “Good to know you recognize the regulations, but there’s no chance of you getting that endorsement from me.” Especially on an unknown cross-country flight, I thought to myself.

“When will you become familiar with the area before your check ride tomorrow morning?” I asked.

William shrugged, again exhibiting his macho attitude. “I don’t really need to know the area in advance. I’ll just figure it out in the morning.”

As William and I discussed these factors, a few other instructors sat on the couch in our pilot lounge, grounded by the winds. I noticed the smirks on their faces as they listened to my questions and William’s answers.

I looked over at them. “Do you think this is a prudent flight plan?”

After a few chuckles, one of them said, “Not a chance.”

William’s face fell with disappointment. He looked around towards all the instructors who were telling him he couldn’t do it. Displaying a bit of anti-authority (Don’t tell me), he insisted, saying, “But I could make it.” “Could and should are two different things,” I responded. William reluctantly decided not to take the flight. I had already known at the start of the day that he wouldn’t be going today.

The only hazardous attitude William did not display for this flight was resignation (What’s the use). And that is because he would not be in a position to resign. I would not allow him to be in the air.

Several days later, William made the cross-country flight, completed his check ride, and earned his private pilot certificate. He went on to earn his instrument, commercial, CFI, CFII, and MEI within 18 months in total and took a job flying Citations.

About a year passed, and William came back to the school to visit. He and I sat down in our pilot lounge, eating some day, maybe week-old cookies, and drank coffee. “How’s life been treating you?” I asked. “Loving it,” William said with a grin. “I occasionally teach new pilots, though that’s never been my full-time gig.”

Our conversation drifted to his attempted cross-country flight when going for his private pilot certificate. We agreed that he went through almost every hazardous attitude for one flight. “I can now see the hazardous attitudes surfacing in my students and sometimes in myself,” William admitted. “That’s the important part, being able to recognize them with the antidote and make the correction.”

I smiled responding, “And that, my friend, is what makes you a good pilot.”